36 Summary and Concluding Remarks

Dr A. P. Shanthi

The objectives of this module are to summarize the various concepts that we have discussed so far in this course on Computer Architecture and to discuss about the future trends.

The basic concepts of Computer Architecture can be beautifully described with the help of the following eight ideas which are listed below. According to David A. Patterson, “Computers come and go, but these ideas have powered through six decades of computer design”. Dr. David A. Patterson is a pioneer in Computer Science who has been teaching Computer Architecture at the University of California, Berkeley since 1977. He is the co-author of the classic texts Computer Organization and Design and Computer Architecture: A Quantitative Approach which we have used throughout this course. His co-author is Stanford University President Dr. John L. Hennessy, who has been a member of the Stanford faculty since 1977 in the Departments of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. These are eight great ideas that computer architects have invented in the last 60 years of computer design. They are so powerful they have lasted long after the first computer that used them, with newer architects demonstrating their admiration by imitating their predecessors. Let us discuss in detail about each one of them.

1. Design for Moore’s Law: The one constant for computer designers is rapid change, which is driven largely by Moore’s Law. Moore’s law, as we have seen earlier, is the observation that the number of transistors in a dense integrated circuit doubles approximately every two years. The observation is named after Gordon Moore, the co – founder of Fairchild Semiconductor and Intel, whose 1965 paper described a doubling every year in the number of components per integrated circuit, and projected this rate of growth would continue for at least another decade. In 1975, looking forward to the next decade, he revised the forecast to doubling every two years. The period is often quoted as 18 months because of Intel executive David House, who predicted that chip performance would double every 18 months, being a combination of the effect of more transistors and the transistors being faster.

Moore’s prediction proved accurate for several decades, and has been used in the semiconductor industry to guide long -term planning and to set targets for research and development. As computer designs can take years, the resources available per chip can easily double or quadruple between the start and finish of the project.

Therefore, computer architects must anticipate where the technology will be when the design finishes rather than design for where it starts.

Moore’s law is an observation or projection and not a physical or natural law. Although the rate held steady from 1975 until around 2012, the rate was faster during the first decade. In general, it is not logically sound to extrapolate from the historical growth rate into the indefinite future. For example, the 2010 update to the International Technology Roadmap for Semiconductors, predicted that growth would slow around 2013, and in 2015 Gordon Moore foresaw that the rate of progress would reach saturation.

Intel stated in 2015 that the pace of advancement has slowed, starting at the 22 nm feature width around 2012, and continuing at 14 nm. Brian Krzanich, CEO of Intel, announced that “our cadence today is closer to two and a half years than two.” This is scheduled to hold through the 10 nm width in late 2017. He cited Moore’s 1975 revision as a precedent for the current deceleration, which results from technical challenges and is “a natural part of the history of Moore’s law.”

2. Use Abstraction to Simplify Design: Both computer architects and programmers had to invent techniques to be more productive, for otherwise design time would lengthen as dramatically as resources grew by Moore’s Law. A major productivity technique for hardware and software is to use abstractions to represent the design at different levels of representation; lower-level details are hidden to offer a simpler model at higher levels. Abstraction refers to ignoring irrelevant details and focusing on higher-level design/implementation issues. Abstraction can be used at multiple levels with each level hiding the details of levels below it. For example, the instruction set of a processor hides the details of the activities involved in executing an instruction. High-level languages hide the details of the sequence of instructions need to accomplish a task. Operating systems hide the details involved in handling input and output devices.

3. Make the common case fast: The most significant improvements in computer performance come from improvements to the common case, i.e. computations that are commonly executed, rather than optimizing the rare case. Rare cases are not encountered often and therefore, it does not matter even if the processor is not optimized to execute that and spends more time. Ironically, the common case is often simpler than the rare case and hence is often easier to enhance. The common case can be identified with careful experimentation and measurement. We have discussed the

Amdahl’s Law that puts forth this idea. Recall that Amdahl’s law is a quantitative means of measuring performance and is closely related to the law of diminishing returns.

4. Performance via parallelism: Since the dawn of computing, computer architects have offered designs that get more performance by exploiting the parallelism exhibited by applications. There are basically two types of parallelism present in applications. They are – Data Level Parallelism (DLP) as there are many data items that can be operated in parallel and Task Level Parallelism (TLP) that arises because tasks of work are created that can operate independently and in parallel. Computer systems exploit the DLP and TLP exhibited by applications in four major ways. Instruction Level Parallelism (ILP) exploits DLP at modest levels using the help of compilers with ideas like pipelining, dynamic scheduling and speculative execution. Vector Architectures and GPUs exploit DLP. Thread level parallelism exploits either DLP or TLP in a tightly coupled hardware model that allows for interaction among threads. Request Level Parallelism (RPL) exploits parallelism among largely decoupled tasks specified by the programmer or the OS. Warehouse-scale computers exploit request level parallelism and data level parallelism. We have discussed in detail about all these styles of architectures in our earlier modules. We have also discussed the need for multi -core architectures, which basically fall under the category of MIMD style of architectures and how such architectures exploit ILP, DLP and TLP. The various case studies of multi – core architectures that we have looked at give us details about which type of parallelism is exploited the most and how.

5. Performance via pipelining: Pipelining is a way of exploiting parallelism in uni-processor machines. It forms the primary method of exploiting ILP. It essentially handles the activities involved in instruction execution as in an assembly line. The instruction cycle can be split into several independent steps and as soon as the first activity of an instruction is done you move it to the second activity and start the first activity of a new instruction. This results in overlapped execution of instructions which leads to executing more instructions per unit time compared to waiting for all activities of the first instruction to complete before starting the second instruction. We have discussed in detail about the basics of pipelining, how it is implemented and also focused on the various hazards that might occur in a pipeline and the possible solutions.

6. Performance via prediction: In some cases it can be faster on average to guess and start working rather than wait until you know for sure, assuming that the mechanism to recover from a mis-prediction is not too expensive and your prediction is relatively accurate. We generally make use of prediction, both at the compiler level as well as the architecture level to improve performance. For example, we know that a conditional branch is a type of instruction that determines the next instruction to be executed based on a condition test. Conditional branches are essential for implementing high-level language if statements and loops. Unfortunately, conditional branches interfere with the smooth operation of a pipeline — the processor does not know where to fetch the next instruction until after the condition has been tested. Many modern processors reduce the impact of branches with speculative execution – make an informed guess about the outcome of the condition test and start executing the indicated instruction. Performance is improved if the guesses are reasonably accurate and the penalty of wrong guesses is not too severe. We have discussed in detail about the various branch predictors and speculative execution in our earlier modules.

7. Hierarchy of memories: Programmers want memory to be fast, large, and cheap, as memory speed often shapes performance, capacity limits the size of problems that can be solved, and the cost of memory today is often the majority of computer cost. Architects have found that they can address these conflicting demands with a hierarchy of memories, with the fastest, smallest, and most expensive memory per bit at the top of the hierarchy and the slowest, largest, and cheapest per bit at the bottom. Caches give the programmer the illusion that main memory is nearly as fast as the top of the hierarchy and nearly as big and cheap as the bottom of the hierarchy. We have discussed in detail about the various cache mapping policies and also how the performance of the hierarchical memory system can be improved through various optimization techniques.

8. Dependability via redundancy: Last of all, computers not only need to be fast, they need to be dependable. Since any physical device can fail, we have to make systems dependable by including redundant components that can take over when a failure occurs and to help detect failures. We have discussed about this in our module on warehouse-scale computers, where dependability is very important.

The challenges associated with building better and better architectures are always there. The ever-increasing performance and decreasing costs, makes computers more and more affordable and, in turn, accelerates additional software and hardware developments that fuels this process even more. As new architectures come up, more sophisticated algorithms are run on them, and these algorithms keep demanding more, and the process continues. We will also have to remember the fact that it is not only hardware that has to keep changing with the times, the software also has to improve in order to harness the power of the hardware. According to E. Dijkstra, in his 1972 Turing Award Lecture, “To put it quite bluntly: as long as there were no machines, programming was no problem at all; when we had a few weak computers, programming became a mild problem, and now we have gigantic computers, programming has become an equally gigantic problem.” We shall elaborate on these issues a little more.

The First Software Crisis: The first challenge was faced in the time frame of ’60s and ’70s when Assembly Language Programming was predominantly used. Computers had to handle larger and more complex programs and we needed to get abstraction and portability without losing performance. That gave rise to the introduction of high level programming languages.

The Second Software Crisis: The time frame was in the ’80s and ’90s, where there was inability to build and maintain complex and robust applications requiring multi – million lines of code developed by hundreds of programmers . There was a need to get composability, malleability and maintainability. These problems were handled with the introduction of Object Oriented Programming, better tools and better software engineering methodologies.

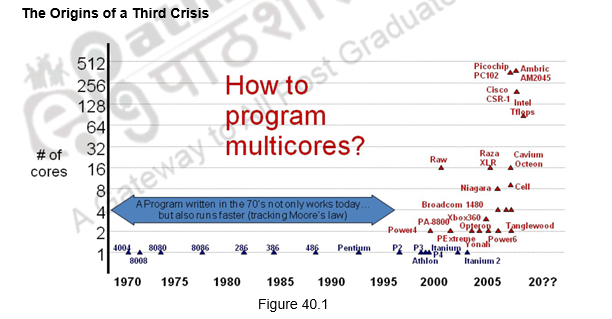

Today, with so much of abstraction introduced, there is a solid boundary between hardware and software and programmers don’t have to know anything about the processor. Programs are oblivious to the processor as they work on all processors. A program written in ’70 using C still works and is much faster today. This abstraction provides a lot of freedom for the programmers. However, we are also facing a third crisis with respect to programming multi-core processors, for the past decade or so. This is illustrated in Figure 40.1.

The Origins of a Third Crisis

The Origins of a Third Crisis: Since the advent of multi-core architectures, we need to develop software that exploit the architectural advances and also sustain portability, malleability and maintainability without unduly increasing the complexity faced by the programmer. It is critical to keep-up with the current rate of evolution in software. However, parallel programming is hard because of the following factors:

• A huge increase in complexity and work for the programmer

– Programmer has to think about performance

– Parallelism has to be designed in at every level

• Humans are sequential beings

– Deconstructing problems into parallel tasks is hard for many of us

• Parallelism is not easy to implement

– Parallelism cannot be abstracted or layered away

– Code and data has to be restructured in very different (non-intuitive) ways

• Parallel programs are very hard to debug

– Combinatorial explosion of possible execution orderings

– Race condition and deadlock bugs are non-deterministic and illusive

– Non-deterministic bugs go away in lab environment and with instrumentation

Ideas on Solving the Third Software Crisis: Experts in Computer Architecture have also pointed out the following directions to solve the present software crisis.

Advances in Computer Architecture: As advancements are happening in the field of Computer Architecture, we need to be aware of the following facts. As pointed out by David Patterson, there is a change from the conventional wisdom in Computer Architecture.

• Moore’s Law and Power Wall

– In contrary to the past, power is expensive now, but transistors can be considered free

– Dynamic power and static power need to be reduced

• Monolithic uniprocessors are reliable internally, with errors occurring only at pins

– As the feature sizes drop, the soft and hard error rates increase, causing concerns

– Wire delay, noise, cross coupling, reliability, clock jitter, design validation,

… stretch development time and cost of large designs at ≤65 nm

• Researchers normally demonstrate new architectures by building chips

– Cost of 65 nm or lower masks, cost of ECAD, and the extended design time for GHz clocks lead to the fact that researchers no longer build believable chips

• Multiplies are normally slow, but loads and stores are fast

– In contrary to the earlier state, loads and stores are slow, but multiplies are fast, because of the advanced hardware – we have a Memory Wall

• We can reveal more ILP via compilers and architecture innovation

– Diminishing returns on finding more ILP – ILP Wall

• Moore’s law may point to 2X CPU performance every 18 months

– Power Wall + Memory Wall + ILP Wall = Brick Wall

All the above factors have led to a forced shift in the programming model.

Novel Programming Models and Languages: Novel programming models and languages are critical in solving the third software crisis. Novel languages were the central solution in the last two crises also. With a paradigm shift in architecture, new application domains like data science and Internet of Things, new hardware features and new customers coming in, we should be able to achieve parallelism with new programming models and languages, without burdening the programmer.

Tools for Parallel Programming: With new programming model and languages coming in, we need to also build appropriate tools to improve programmer productivity. We need to build aggressive compilers and tools that will identify parallelism, debug parallel code, update and maintain parallel code and stitch multiple domains together.

Thus, while all consumer CPUs are now multi-core, software is still designed as mainly sequential. The parallelisation of legacy code is very expensive and requires developers with skills in both computer architecture and application domain. We need a new generation of tools for writing software, backed by innovative programming models. New tools should be natively parallel and allow for optimisation of code at run-time across the multiple dimensions of performa nce, reliability, throughput, latency and energy consumption while presenting the appropriate level of abstraction to developers. Innovative business models may be needed in order to make the development of new generation tools economically viable.

Future Trends: Based on the discussions provided above, in future, we can expect that hardware will become a commodity and the value will be in the software to drive it and the data it generates. The data deluge will require an infrastructure that can transfer and store the data, and computing systems that can analyze and extract value from data in real time. According to the roadmap provided for computer systems, there are arguments suggesting that the computing sector will become increasingly polari zed between small application-specific computing units that connect to provide system services, and larger more powerful units that will be required to analyze large volumes of data in real time.

Applications in automation, aerospace, automotive and manufacturing require computing power which was typical of supercomputers a few years ago, but with constraints on size, power consumption and guaranteed response time which are typical of the embedded applications. Therefore, we need to develop a family of innovative and scalable technologies, powering computing devices ranging from the embedded micro-server to the large data centre.

Computing applications merging automation, real-time processing of big data, autonomous behaviour and very low power consumption are changi ng the physical world we live in, and creating new areas of application like e.g. smart cities, smart homes, etc. Data locality is becoming an issue, driving the development of multi -level applications which see processing and data shared between local/mobile devices and cloud-based servers. The concept of Internet of Everything is developing fast.

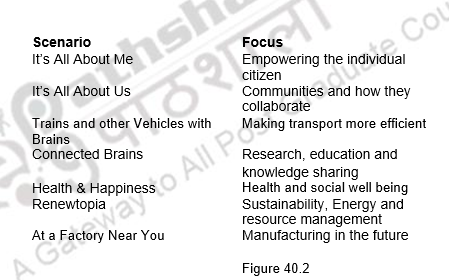

The roadmap points out several scenarios that address critical aspects of society and economy. Figure 40.2 gives an overview of scenarios. Describing how computing will evolve in each of the scenarios will allow us to describe a series of technology needs that could translate into research and innovation challenges for the computer industry. A common theme across all scenarios is the need for small low-cost and low-power computing systems that are fully interconnected, self-aware, context-aware and self-optimising within application boundaries.

To summarize, we have summed up the concepts discussed in this course on Computer Architecture. We have pointed out the basic ideas that need to be remembered and the major challenges that we are facing today.

Web Links / Supporting Materials

- Computer Architecture – A Quantitative Approach , John L. Hennessy and David A. Patterson, 5th Edition, Morgan Kaufmann, Elsevier, 2011.

- Computer Organization and Design – A Hardware/Software Interface David A. Patterson and John L. Hennessy, 5th Edition, Morgan Kaufmann, Elsevier, 2014.

- Next Generation Computing Road Map: ISBN 978-92-79-37580-4, Europian Union, 2014.